|

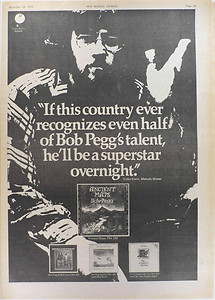

| Bob Pegg, me & Anne, Warrington, 1979. |

This week’s

interviewee is someone whose career I have been following since the 1970’s, as

you might guess from the photographs. Bob Pegg is many things, one

of the best songwriters this country has ever produced, a skilled musician, a

story teller, an author, a researcher into the folklore of these islands, a

historian – oh the list goes on. I first saw him on a late night television programme

from a pub in Manchester, his band, the magnificent Mr. Fox were filmed live,

for a short programme, the other band on was if I remember correctly The

Natural Acoustic Band. That would be around 1970/1. I did not see him live

until 1977 at the first July Wakes Festival (incidently one of the best festivals I have

ever been to). By then Mr Fox had imploded-acrimoniously, it would have been near

impossible for a group of such talent and vision not to have crashed and burned,

they were the Buffalo Springfield of 70’s English folk rock, the best of the bunch, bold, original and truly mesmerising. Bob's website.

But there is more to Bob than Mr Fox, Folk published in 1976 predates Imagined Village and Electric Eden and examines what we mean by the term folk music. Bob has released

many albums over the years and more books. He was someone I always went to see when i had the chance and I never saw a bad gig. However as the 1980’s ground inexorably into the

90’s Bob moved to Scotland and became a part time arts worker. I moved to the south west and lost

contact with him sometime after he appeared at my university, I’d booked him

when I was President of the Student’s Union and he and Julie Fullerton gave an unforgettable

performance. Sadly, the person in charge of the video/recordings of the night disappeared

never to be seen again.

|

| Bob and Barry |

I could big up Bob for hours, he is one of the touchstones of my musical landscape. I cannot recommend strongly enough that you listen to his work, here’s a track by Mr Fox.

How did you begin to write?

In the first or second year at Grange Primary School

There are big ships and little ships

And there are all kinds of ships

Some take us trips to far off lands

Some take us trips far from the sands

Something along those lines. Mrs Barsby, who could make you

cry just by looking in your direction, said she liked it – which gave me

confidence to do more writing. Amazing, even at such an early age, what a difference

someone’s approval can make.

The idea of writing songs came much later, I think, in the

early 1960s. I was still at school, and a regular of the Nottingham Folk

Workshop, one of the earliest British folk clubs. The Folk Workshop had a great

range of performers: Hope Howard, who came from the West Indies, and sang

calypsos and spirituals; Quentin Hood, a dashing balladeer; bearded Sonny Ford,

who worked at a gas station, wore cowboy boots, and worshipped Rambling Jack

Elliott; Carole Butler, my future wife; and Spike Woods, who wrote songs which

were influenced by his Catholic faith. One of Spike’s songs in particular was

very popular. It was called When the Big Bird Comes. Later, Carole and I adopted

it into our own repertoire; and I think it was Spike’s example that gave me the

idea to write a song, together with having heard Ewan MacColl, Charles Parker

and Peggy Seeger’s original Radio Ballads – particularly The Ballad of John

Axon, Singing the Fishing and The Big Hewer, which were broadcast on the Home

Service in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s. They included some wonderful songs by

MacColl which endeavoured to incorporate the speech rhythms and phraseology of

the people who worked in the industries that the programmes dealt with: the

railways, fishing, coal mining.

So I came up with Nottingham Town

What influences your work?

Early memories are of my Mum reading to me from Palgrave’s

Golden Treasury. My favourite poem began:

What was he doing, the great god Pan,

Down in the reeds by the river?

It’s by Elizabeth Barratt Browning, and it’s called A

Musical Instrument. Musical instruments (especially ancient ones like the

panpipes), narratives (what happens next?), strange and mythological creatures,

are all now part of my life and work as a musician, storyteller and writer.

At Grange Primary one of my favourite times was when the

whole school gathered together in the hall to sing folk songs. Songs like The

Raggle Taggle Gypsies, and The Golden Vanity – bold tunes, and stories of

adventure, bravery, passion, betrayal. It’s easy to mock those Folk Songs for

Schools sessions, with their rather relentless piano accompaniments – and I

know they put many people of my generation off folk songs for the rest of their

lives – but I used to love them.

At Nottingham

High School

Alan showed us all by example that, in grey times, it wasn’t

necessary to be a grey person. Ted Davies was a fan of both contemporary

English writing and film. A lesson was as likely to be concerned with the relative

merits of the novel Room at the Top and its film version (great film, crap

book, was Ted’s verdict) as with anything directly linked to the curriculum. In

the late ‘50s and early ‘60s Nottingham had

three art house flea-pits, as well as at least the same number of big, mainstream

cinemas. My home town of Long Eaton

had The Empire, The Scala, and The Palace (where my Dad worked when he was in

his teens as an assistant projectionist). From the moment I was allowed in

unaccompanied, I would go to “the pictures” two or three times a week,

uncritically enjoying everything from John Ford to Truffaut, through Kubrick,

Antonioni, Bergman, Cassavetes, Fellini, Hawks, Wajda, Godard, and lots of the

other great directors who were banging out movies in those days. Film had an

enormous influence on my songwriting. When I wrote the songs, and when I sang

them, I would be aware of a screen in my head, seeing them as moving images.

There are lots of other influences: Methodist hymns; Grimm’s

fairy tales; the music and lyrics of Arthur Sullivan and W S Gilbert; T S

Eliot’s poetry; Basil Bunting’s poem Briggflatts (and the peace of Briggflatts

itself, a Quaker Meeting House near Sedbergh); the music of early Fairport

Convention; Scottish, Irish and English Traveller storytellers and singers;

Sinfonye, a medieval revivalist band; the poet George Macbeth; Jack Kerouac,

particularly On the Road; Nick Strutt, who taught me how rich and complex is

the world of Country Music; Bill Leader, the legendary folk record producer.

It’s a long list, but I’d like to give a special mention to the late Warren

Zevon, who wrote and recorded so many wonderful songs. If I want cheering up,

odds are I’ll put on some Warren ,

and sing along to Roland the Headless Thompson Gunner, or Play It All Night

Long, his riposte to Lynyrd Skynyrd’s Sweet

Home Alabama

Gran’pa pissed his pants again

He don’t give a damn

Brother Billy has both guns drawn

He ain’t been right since Vietnam

Sweet home, Alabama

Play that dead band’s song

Turn those speakers up full blast

Play it all night long

After the interview Bob wrote to me to say he'd forgotten to mention two people who have influenced him for most of his life Charles Fort and Alfred Watkins, he of The Old Straight Track.

Where do the ideas come from?

Early on, in my twenties, the ideas definitely come from

some mysterious place, presumably a storehouse where all the bits and pieces

had been accumulating and cross-fertilising since I was little. The opening of

the storehouse doors, if you like, was Bill Leader offering Carole Pegg and I a

contract, in 1969, to record for his Trailer label. From then on I began to write

songs, and kept going on doing so through the next decade, never wondering whether

the stuff would stop tumbling out. The fact that there was always another

record to be made was a great stimulus. There were so many ideas for songs. The

story for The Gipsy, the title track of the second Mr Fox album, came to me as

I was driving round a roundabout in Stevenage ,

where I taught English for a year before Carole and I formed the band. I wrote

the lyrics for Dancing Song, from the same album, in an hour or so, lying on a

bed in our rented house in Stevenage

Old Town

There was a time in the 1970s when I stopped writing songs

for a while, because the apparently fictional scenarios seemed to be predicting

what would happen to me (none of it good).

A short, alternative answer to the question, is that place

influences my work: the two Mr Fox albums were informed primarily by the Yorkshire

Dales; Bob Pegg and Nick Strutt by Leeds, Lancashire and Cumbria; The

Shipbuilder by North Yorkshire; Ancient Maps by the landscape of Alfred

Watkins’ book The Old Straight Track; Bones, again by North Yorkshire; the

songs on The Last Wolf by the Pennine Dales, and by the Highlands of Scotland. My

recent book, Highland Folk Tales (The History Press 2012), which comes out of

my work as a storyteller living in the Highlands ,

links the stories to the places that have given them homes, and to journeys through

the physical landscape between those places.

Lastly, it occurs to me that the lives of other people have

always inspired me. A lot of the songs I wrote for Mr Fox were taken from

stories I had heard from people who lived in the Yorkshire Dales, the same goes

for the Calderdale songs and the memories of the inhabitants of the West

Yorkshire Pennines.

Which comes first lyric or music?

Could be either. Sometimes a bit of a tune will pop into your

head, and you think, “I quite like that”. Best to note it down immediately, or

inevitably it will slip away (these days I always have a notebook with me). You

may never use that tune; in a week’s time it may seem utterly banal. But it

might become the basis for a composition or a song at some time in the future.

A lot of my songs are narratives, in ballad form, and they usually rhyme (a

writing habit I’ve tried to break free of, but always seem to come back to), so

it often makes sense to write the lyrics first – though a melody will probably

suggest itself as you’re putting down the words. But there’s usually nothing

particularly subtle or sophisticated about the tunes, though I tend to put in a

bit of effort to keep them simple.

And on the odd occasion a fragment of a lyric will pop up

with a tune already attached.

What advice would you give to anyone starting out?

Just get on with it. Things have changed so much during the

time when I started out and now. You can become a famous and successful

musician without leaving your bedroom. You no longer need to be in thrall to

the record company, and sign away your life. Though at the same time you, or

your agent/manager, need to be very skilled in contemporary promotion

techniques – social media and so on.

When I started off in the music industry, in the early 70s,

there was a lot less music released on an annual basis than there is now. All

the different stages of issuing and promoting an LP were controlled by

specialists – recording studios, mastering, pressing, sleeve design and

printing, promotion, distribution. Now you can do it all on your laptop. But at

the same time the competition is probably much greater. Within a very short

period of time Mr Fox, coming pretty much out of nowhere, had signed up with

Translantic Records, made their first album, debuted at the Royal Festival

Hall, got loads of publicity – half a page feature in the Guardian, awards (Melody

Maker Folk Album of the Year, I think) – John Peel and other radio sessions, a

BBC1 documentary. I’m sure that now it’s possible under your own steam to reach

at least a certain level of success, in terms of people being able to access

your music and information about it and you, that in my day would have been

inconceivable without your being supported by the machinery of a record label,

or being individually wealthy. And that elusive thing talent often has a part

to play.

For someone like me, who needs a periodic shot of positive audience

interaction, the best thing you can do is just get out and do whatever it is

you do. Go to open mic sessions, perform for free at local festivals, busk, set

up our own gig in the café down the road, and put everything you can into

promoting it. You’ll be doing it all anyway, and lots of other things too.

I would also suggest to any young singer/songwriter that

they be more circumspect in airing their opinions than I was at their age. I

managed to upset just about everybody, and it did my career no good at all.

Though, of course, if I were to offer this advice, any young singer/songwriter

worth his or her salt would probably tell me to bugger off.

How many songs have you written that you have not

recorded?

Quite a few. There’s a long song sequence called The Ballad

of Wayland Smith, which I wrote, and performed a few times, back in the late

70s. It’s quite a tough story, with some extreme violence and a rape, and I

attempted to set the old legend in a post-apocalyptic future. In the mid 80s

Taffy Thomas and I talked about the possibility of a large-scale outdoor

version set by the White Horse of Uffington, the chalk hill carving in

Oxfordshire, which is by the prehistoric track known as The Ridgeway, and close

to the long barrow called Wayland’s Smithy. At the end of the show, Wayland,

who in the story escapes from captivity by flying off on a set of gold wings

he’s been secretly building, would launch himself from the White Horse on a

hang glider into the valley below. It wasn’t an entirely improbable scenario,

as Taffy’s theatre company Charivari had already staged a big outdoor

production of my song sequence The Shipbuilder for two thousand people over two

nights on the beach at Whitby

during the Folk Week. But it never quite got beyond enthusiastic discussion.

There are also lots of unrecorded songs going right back to

the 70s and up to the present. Enough for a couple of albums of stuff that I’d

be happy to see the light of day.

What’s in the pipeline?

There are a couple more books for The History Press. The

Little Book of Hogmanay has a March 2013 deadline, and Folk Tales of Argyll is

due to be handed in a year after that.

I’ve written the music for Graham Williamson’s documentary

film, Heads!, about mysterious Celtic Stone Heads. There’s already a trailer on

YouTube, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gd8-61Froi4&feature=player_detailpage

and I’m looking forward to seeing the whole thing.

Every Picture Tells a Story, an exhibition of very large

prints of John Hodkinson’s black and white illustrations for my Highland Folk

Tales book, was launched on 16th November in The Stables gallery in

Cromarty. For three days I was installed in the gallery, telling the stories

behind the images, as well as playing music on my Native American flutes,

ocarinas, jaw harps, etc. My partner, Mairi MacArthur, and I did all the

promotion and publicity ourselves.

There’s been a long-standing offer from The Folk Police

label to put out a CD of songs, which I hope to take up soon – though I’ve been

saying this for three or four years now.

Probably an ancient Gaelic song, sung at night by a Tinker

camp fire, somewhere among the hills of the Highlands

in the early 1950s, just at the time when the old, semi-nomadic Traveller way

of life was coming to an end. I would enjoy being breathed out on to the night

air, to join the smells of the burning wood and peat, the tobacco smoke, and

the aroma of whiskey from a tin mug.

Pure poetry, thanks

Bob.

I thought I’d share

with you the programme to the 3rd Warrington Revelry from 22nd

September 1979 at which Bob performed and where I took the photographs. I happened to find it in my parents loft when we were clearing out the house following my father's death.

|

| I love the description of Mr Fox as "ill-fated" |

Wow - what a cool talented guy. I just love the lyrical swing of Ancient Maps. Not sure I would have known you from the photo!

ReplyDeleteAncient Maps was critically praised and is an interesting album. All his recordings are worth a listen

DeleteGreat interview!

ReplyDeleteIt was cool to see the program and photographs, too.

Thanks. The programme looks of its time, the olden days before desktop publishing. And the photos are fun.

Delete